Nearly 6 years later and the use of digital technology has accelerated at an incredible pace. Many educators are using scratch and makey-makey like it is no big deal. Others are using 3D printing, laser cutters and virtual reality in their day-to-day practice. So much has happened! However, I recently went on a hunt to find some blog posts that describe how various educators are using these new fandangled tools in their classrooms. I remember spending hours in 2012 pouring over the many posts about how others were using e-learning, byod, etc. in their classrooms. While I am sure that there are many out there, it was much harder to find recent posts than what I anticipated! Perhaps this is because we have passed the 'popularity' phase of e-learning. We are no longer concerned with the latest and greatest cool tool on the block, and have become increasingly focussed on the deeper learning? How do we use e-learning to amplify learning, not just use technology for technology's sake? In response, I thought I would share some of the tools that I use now. Of course, my pedagogy has evolved massively since the time of my first post. Here is a brief snapshot of the tools I use now and the pedagogy/theory that underpin them.

Fuelled by my role at Hobsonville Point Secondary School where the students are flying the plane and I am just the air traffic controller, I needed something to help me manage all the independent projects that were happening at any given moment. This can be a real juggle, especially when there are delayed flights (students not making enough progress), flights that arrive early (students making really fast progress), multiple flights arriving at once (many students needing your attention all at once) and emergency flights (urgent things that need to be addressed eg. inappropriate behaviour). I use a number of tools to help me manage the project based, personalised and autonomous learning environments that I strive to create.

Every lesson begins with a do now in the Google Classroom. Every lesson begins with a self-explanatory 'DO NOW' so that students can come to class and get started on the learning without me. This gives me time to do the roll, talk to late students, check in with students who were away, etc. The whole lesson and learning objective is also outlined in the Google Classroom along with the relevant resources. This means that students who are away can catch up on their learning. Students who finish activities quickly can also move on to the next task. We also add the rubrics and assessments in the about section of the Google Classrooms. Our use of Google Classroom is largely informed by our original HPSS e-learning best practice guide. You will see the influence of assessment for learning and universal design for learning quite heavily in this document. The image below shows the 'should do' section of our best practice guide.

My use of Google Classroom and our best practice guide has been heavily informed by:

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. Guilford Press.

- Absolum, M. (2011). Clarity in the classroom: Using formative assessment for building learning-focused relationships. Portage & Main Press.

- Voice of our students.

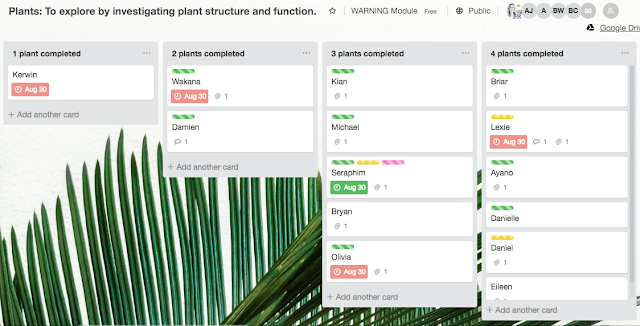

Trello is without a doubt my favourite tools to manage my air traffic controller role. Trello allows me to quickly identify students who are behind or ahead, students who need help, students who are struggling, etc. I set up the tasks students need to work through in each column and the names of the students/groups as cards. As students complete activities, they simply move their cards along. I have even used Trello for assessments since the cards allow you to attach files, set due dates on tasks, add comments, and track your interactions on the board. We also use the labels to signpost if students need help or are making progress.

The reason why Trello is without a doubt one of my favourite classroom e-learning tools is that it facilitates the kind of autonomous student learning environment that I am working hard to develop. Additionally, using this tool in conjunction with agile and scrum has meant that it can also be used to facilitate collaboration as it allows students to see their contributions, progress and involvement.

The latest tool that I have been using is Kialo. The website attempts to do "empower reason through friendly and open discussions." While there are some interesting debates happening on the platform, I have found it's the greatest merit the ability to map out perspectives, evidence, opinions and claims for an argument. Not only can you find some great examples of how to structure an argument, but you can also build your own. We have really enjoyed how everyone in the class can find ways to contribute, whether it is through adding their own claims or evidence to an argument, or whether it is through voting on the impact of others' claims. Additionally, after building an argument collectively as a class, you have created a digital, collaborative artefact to act as a resource for future use.

My use of Kialo has been informed by:

As I wrote this post, it struck me just how much my pedagogy has evolved. I have become increasingly focused on translating academic and scholarly work into a workable classroom version. (That means I genuinely enjoy having a good debate about epistemological integrity and then working out what that could and should mean for the class I am teaching this week.) I also recognise some of the early elements of my practice that are still present too. For example, I still think that saving time is a key filter for the tools I use. Electronic grade books, automarking and productivity tools are all a key strategy to juggle the many demands of being a teacher. The time I freed up by getting Flubaroo to mark the quiz was time I could spend on high quality feedback instead!

The reason why Trello is without a doubt one of my favourite classroom e-learning tools is that it facilitates the kind of autonomous student learning environment that I am working hard to develop. Additionally, using this tool in conjunction with agile and scrum has meant that it can also be used to facilitate collaboration as it allows students to see their contributions, progress and involvement.

My use of Trello has been influenced and inspired by:

- Adkins, L. (2010). Coaching agile teams: a companion for ScrumMasters, agile coaches, and project managers in transition. Pearson Education India.

- Facer, K. (2011). Learning futures: Education, technology and social change. Routledge.

|

| Trello |

The latest tool that I have been using is Kialo. The website attempts to do "empower reason through friendly and open discussions." While there are some interesting debates happening on the platform, I have found it's the greatest merit the ability to map out perspectives, evidence, opinions and claims for an argument. Not only can you find some great examples of how to structure an argument, but you can also build your own. We have really enjoyed how everyone in the class can find ways to contribute, whether it is through adding their own claims or evidence to an argument, or whether it is through voting on the impact of others' claims. Additionally, after building an argument collectively as a class, you have created a digital, collaborative artefact to act as a resource for future use.

My use of Kialo has been informed by:

- Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2010). A brief history of knowledge building. Canadian Journal Of Learning and Technology, 36(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21432/T2859M

- Hipkins, R., Bolstad, R., Boyd, S., & McDowall, S. (2014). Key competencies for the future. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press.

- Gilbert, J. (2005). Catching the knowledge wave? The knowledge society and the future of education. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

- Gilbert, J. (2007). Knowledge, the disciplines, and learning in the Digital Age. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 6(2), 115-122. doi:10.1007/s10671-007-9022-1

|

| Kialo |

As I wrote this post, it struck me just how much my pedagogy has evolved. I have become increasingly focused on translating academic and scholarly work into a workable classroom version. (That means I genuinely enjoy having a good debate about epistemological integrity and then working out what that could and should mean for the class I am teaching this week.) I also recognise some of the early elements of my practice that are still present too. For example, I still think that saving time is a key filter for the tools I use. Electronic grade books, automarking and productivity tools are all a key strategy to juggle the many demands of being a teacher. The time I freed up by getting Flubaroo to mark the quiz was time I could spend on high quality feedback instead!

So my education friends... I am curious what e-learning tools you use now and why? What is it that has stood the test of time for you? Perhaps it's time for a circa 2014 chain blogging event? Tag three people to share their #edtechevolution?

PS: Some other tools I have used recently include Playposit, Google Cardboard, Kahoot, Quizizz, Google Maps, Google Earth, Google docs/sheets/presentations/drawings, Piktochart, YouTube, Socrative, videonot.es, Read Write for Google, Equatio, iQualify, Khan Academy, Soundcloud, Garage Band, iMovie, Screencastify and so many more!